This report examines the laws and policies that shape food in New England’s publicly operated correctional facilities. It offers recommendations for advocates and policymakers to ensure nutritious and safe meals while improving how prison food is sourced and served.

Introduction

Approximately 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States. While law- and policymakers have focused some attention on improving conditions for individuals who are incarcerated, the issue of food in prisons has not been at the forefront of prison policy reform. In recent years, there has been increased attention focused on this issue in New England—a region marked by some successful efforts that reduced costs, increased access to fresh local foods, and provided skills and training. Many correctional officials and food service managers in the New England region and beyond are working hard with limited means in a policy landscape that often makes it difficult to increase the quality of prison food. This report is intended to assist policymakers, correctional facility administrators, food service managers, food justice advocates, and the public in understanding the complex set of constitutional, federal, and state laws and policies impacting the prison food system to identify opportunities for reform in the New England region.

People of color are disproportionately represented in the prison population; incarceration rates are 1.3 to 6 times higher for people of color than for white people. Notably, Black Americans comprise 38 percent of the prison population despite constituting 13 percent of the US population. In some New England states these disparities are even more stark. Both Connecti- cut and Maine maintain a disparity of 9:1 between Black and white individuals who are incarcerated, and Massachusetts leads the country in ethnic disparities. While poverty represents both a substantial cause and effect of incarceration, many individuals who are incarcerated also demonstrate additional factors of socioeconomic marginalization, including food and nutrition insecurity, low educational attainment, and high unemployment rates, as compared to the general population. In the US, rates of food insecurity and very low food security are “significantly higher than the national average” for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic households. Consequently, for Black individuals who are incarcerated, food insecurity may present a challenge prior to, during, and after incarceration. Additionally, since many individuals continue to experience food and nutrition insecurity upon release due to difficulty securing employment, the health impacts can be ongoing.

“Food insecurity means that households were, at times, unable to acquire adequate food for one or more household members because they had insufficient money and other resources for food.”

— United States Department of Agriculture, Household Food Insecurity in the United States in 2021 https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/104656/err-309.pdf?v=9154.3

Much public attention focuses on privately owned prisons, yet less than eight percent of the prison population is housed in them. In fact, most individuals who are incarcerated are held in publicly operated federal or state prisons, facilities which are often required to follow procurement policies and guidelines for purchasing food. This provides an opportunity for states to consider developing procurement policies directed at the same goals as other institutional procurement policies: economic development through local preference and improved health outcomes.

Nutritional inadequacy negatively impacts the health and well-being of incarcer- ated individuals during their incarceration and after release. Nutritionally deficient meals, often containing high amounts of processed carbohydrates, contribute to diet-related illnesses such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease and unsanitary meals frequently lead to foodborne illness outbreaks. Indeed, a study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that incarcerated people were six times more likely to contract a foodborne illness than individuals outside the correctional system. Moreover, a greater proportion of the population that is incarcerated experiences chronic illness than the general population—44 percent versus 31 percent, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Reports have shown that prison food can be undesirable and unsafe, lacking in nutritional quality, flavor, variety, and sanitation. From sourcing, quality, and safety to the environments where food is served and eaten, the correctional food system often fails to provide people who are incarcerated with health, safety, and dignity. Prison halls can be crowded, loud, lacking natural light, heavily monitored by armed guards, and uncomfortably hot or cold. These conditions can exacerbate a negative relationship with food and negative mental health outcomes, as well as create hostile eating environments. In some instances, poor food quality has fueled riots and hunger strikes demanding healthier and safer meals.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented additional challenges after some states were bound by regulations or directives that required lockdowns or closures of dining halls. Reports indicated that some incarcerated individuals were confined up to 23.5 hours per day in their cells during this period and could not access the commissary

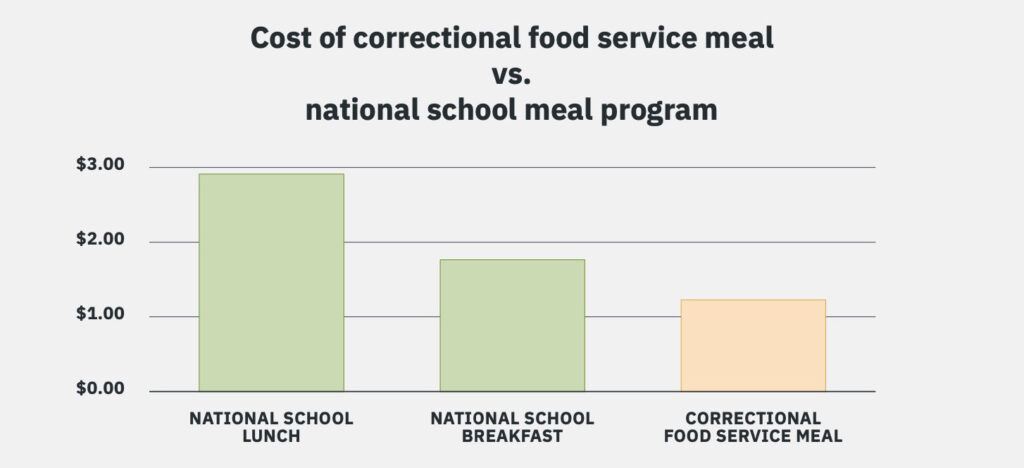

These challenges can be attributed, in part, to correctional budget allocations and competi- tive bidding processes that pressure administrators and food service operators to prioritize cost savings above other considerations. Predictably, however, these austerity measures can result in poor quality and nutritionally inadequate food offerings. Cost reductions that result in nutritionally inadequate food may ultimately cost taxpayers more as healthcare in public prisons constitutes their largest expenditure—estimates suggest these costs amount to over $12 billion per year. Across the country, states have responded to budget shortfalls by reducing expenditures on corrections, impacting correctional food system funding (an already small portion of corrections’ overall budgets). A few states in New England—Connecticut, Massa- chusetts, and Rhode Island—reduced their corrections budgets over the past few years while Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire have increased theirs. As discussed in Part III of this report, New England states allocate $3.70 on average per incarcerated individual per day for correctional food service. This equates to roughly $1.23 per meal. By way of comparison, the average cost per meal provided through the National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program in school year 2016-2017 were $2.92 and $1.76, respectively.

Cost reductions that result in nutritionally inadequate food may ultimately cost taxpayers more as healthcare in public prisons constitutes their largest expenditure—estimates suggest these costs amount to over $12 billion per year.

Terminology

The language used to describe identities changes over time and differs by context and personal preference. While there are many terms used to describe people who are or have been incarcerated throughout history and across industries—inmate, prisoner, offender, felon, convict—the authors have chosen to use people-first language throughout this report. People-first or person-first language aims to describe what a person “has” or what situation a person may be in (for example, person experiencing houselessness) as opposed to describing what a person “is” (for example, homeless). In this report, authors use the term “individual who is incarcerated” to describe people who are or have experienced confinement within a correctional facility. The authors recognize, however, that this language is not necessarily accepted or desired by all people familiar with correctional systems. Further, while the language of incarceration may have changed socially or culturally, federal and state laws and policies still commonly use terms such as “inmate” to describe persons in custody of federal and state correctional systems. When directly quoting a law or policy, authors will use the term provided by the legal language.

For more about the history and impact of people-first language in incarceration, see Alexandra Cox’s article, The Language of Incarceration.

New England states could take a cue from their other strong local procurement initiatives to meet multiple state goals and priorities, including improved health outcomes and support for locally and sustainably produced food. At least one Maine correctional facility has been lauded for its efforts to grow produce for meals at the facility while providing training and some degree of respite from the danger and boredom of prison. However, programs like these are rare and for those that do exist, most must give the produce away due to restrictions in contracts with food service companies, food safety regulations that require the produce to be inspected, or because the program does not yield enough produce to feed the facility’s entire population. Additionally, the success of these programs relies on consistent labor and some correctional systems have long exploited individuals who are incarcerated for cheap agricultural and food service labor; while wages vary across the United States, they are typically very low, ranging from $0.30 to $7.00 per hour.25 In New England, individuals who are incarcerated are often compensated less than $1.50 per hour for agricultural and food service work.

Efforts are underway, many at the state and local level, to address some of these problems and their consequences. However, the legal landscape governing prison food is complex—for advocates seeking to advance law and policy reform to address these issues, it is useful to understand both the relationship between and the application of constitutional, federal, and state law. Since over half of all people incarcerated in the US are currently held in state prisons, state law and policy reform is a strategic and impactful leverage point to improve meals for millions of incarcerated individuals. While the issue of food in correctional facilities only scratches the surface of the many structural problems within the US criminal justice system, it does address a fundamental human need for individuals in prisons.

This report identifies relevant federal and state laws to contextualize the governance of state prisons within the broader United States correctional system and details the laws and regulations that govern food production, procurement, preparation, and consumption in New England state prisons. Additionally, this report include sexamples from state correctional manuals and policies in New England and provides a comparative analysis of relevant laws, regulations, and policies alongside correctional industry standards. There may be variations in how these laws, regulations, and policies are interpreted and implemented by the responsible entities.

Since over half of all people incarcerated in the US are currently held in state prisons, state law and policy reform is a strategic and impactful leverage point to improve meals for millions of incarcerated individuals.

While some of the policies included here may appear to address existing concerns, they can only do so if implemented and enforced. To maintain a focus on state laws and regulations, this report does not analyze privately run correctional facilities or county jails. Though the analysis focuses on the New England region, practitioners in other states can use these examples to identify and evaluate the legal frameworks that govern correctional food systems in other states. This report concludes with a set of recommendations for advocates and policymakers to consider as they address these issues that can carry long-term impacts for individuals who are incarcerated.

Acknowledgments

This report was produced by the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law and Graduate School, in partnership with Farm to Institution New England. We thank the following people for reviewing this report: Jessi Silverman, MSPH, RD, Senior Policy Associate, Center for Science in the Public Interest; Leslie Soble, Senior Program Manager, Impact Justice; Peter Allison, Executive Director, Farm to Institution New England; Brittany Florio, Program Coordinator, Farm to Institution New England; Hannah Leighton, Director of Research and Evaluation, Farm to Institution New England; and correctional commissioners, managers, food service directors, and others across New England. Your feedback was invaluable.

This report would not have been possible without the tremendous production and communications support of the following staff at the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems: Lihlani Skipper Nelson, Deputy Director; Claire Child, Assistant Director; Whitney Shields, former Project Manager; and Molly McDonough, Communications Manager. Thank you to Research Assistant Luis Gonzalez for outstanding citation support.

Thank you to Sam Bruchez for designing the report. Cover image is by Brian Hindson, an artist who is currently incarcerated in Texas. Thank you to the Justice Arts Coalition for facilitating use of the artwork.

Suggested Citation

Laurie J. Beyranevand et al., Vt. L. & Grad. Sch. Ctr. for Agric. & Food Sys. & Fine Farm to Inst. New Eng., The State of Prison Food in New England: A Survey of Federal and State Policy (Apr. 2023), https://www.vermontlaw.edu/sites/default/files/2023-04/state-prison-food-new-england.pdf.