This report examines the legal and regulatory framework for preventing, detecting, and enforcing against seafood fraud, and makes recommendations for policymakers to address the issue of seafood fraud both domestically and abroad.

Introduction

Advances in food production across the globe have led to a remarkably complex and uncoordinated global supply chain marked by limited transparency and traceability. This has increased incidences of food fraud, sometimes with devastating consequences. A recent survey conducted by the International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN), managed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), indicated that food safety authorities and regulators around the globe need information and best practices to address food fraud. Industry has also attempted to respond to the issue through private mechanisms related to food safety, vulnerability, and defense. Food fraud in the seafood sector is particularly rampant due to the many drivers that cause individuals to consider fraud coupled with the ample opportunities presented by the complexities in the seafood supply chain. Seafood fraud implicates myriad policy concerns, including food safety and public health, consumer trust in the seafood industry and the corresponding responsible regulators, the viability of law-abiding fishers’ livelihoods, countries’ international reputations in the global fishing industry, and ongoing national and international conservation efforts and fishery management. Among types of food fraud, seafood fraud is distinct due to its close connection with natural resource management.

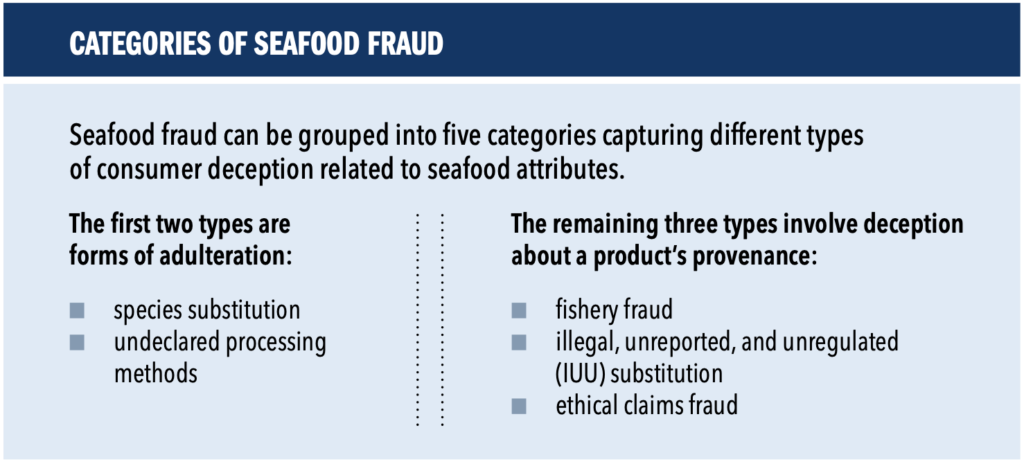

Each type of seafood fraud confers economic gain on the fraudster, either from selling a lower quality product at a higher price or by avoiding costs. The extent of fraud in the seafood sector is difficult to ascertain because much fraudulent activity likely goes undetected. However, several studies in multiple countries have uncovered high rates of mislabeled seafood species. Given the significant seafood market share associated with popular seafood products, even low rates of some mislabeled products may result in consumers purchasing significant quantities of fraudulent seafood.

FAO’s most recent estimate puts global fish and seafood production at 172.6 million tons, with approximately 54 percent coming from capture production and the remaining 46 percent from aquaculture. Over one-third of all fish production enters international trade. In some countries, the proportion of seafood coming from international supply chains is much higher; in the United States, over 80 percent of all seafood is imported. It is not uncommon for seafood to pass through a country of harvest, a separate country of processing, and a third for sale and distribution to consumers. In some cases, domestic seafood is exported to another country for processing, then reimported to the original harvesting country for sale. These complex and opaque supply chains provide multiple opportunities for individuals and entities to engage in fraud.

This report examines the issue of seafood fraud with a particular emphasis on the United States to provide a set of recommendations for states attempting to address the issue. Consequently, the report includes discussion of key US laws, regulations, and programs that operate together as an informal seafood fraud prevention and detection framework. As will be discussed later, there are both benefits and consequences associated with this conceptual approach used by the United States. The report concludes with a set of recommendations and considerations for policymakers related to the legal meaning of seafood fraud, prevention and detection, enforcement, and measures tailored to the complexities of the seafood supply chain.

Acknowledgments

This report was produced by the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School, with support from the National Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, and US Department of Agriculture. Research for this report was funded in part by FAO. Views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of institutional funders.

The report would not have been possible without the assistance, cooperation, and production support of the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems: Claire Child, Assistant Director; Molly McDonough, Environmental Communications Specialist; Lihlani Nelson, Associate Director; and Whitney Shields, Project Manager. In addition, we thank the following individuals for their assistance and support: Max de Faria MFALP’22 and Jenileigh Harris MFALP’18.

The report benefited from significant research, writing, and editing support from Cydnee Bence JD’20, LLM Fellow, Center for Agriculture and Food Systems, Alexia Basile MFALP’19 and Paige Beyer JD’21.

We would like to thank the following reviewer for providing feedback on an early draft of this report. Reviewers do not necessarily concur with the report’s recommendations but advised on portions of its content: Meghan Jeans, Foghorn Strategies.

The authors gratefully acknowledge participants in FAO’s 2019 expert meeting on food fraud. Discussions from that meeting have informed our thinking on legal and enforcement approaches to this issue.

Finally, we would like to thank those who were interviewed prior to and during the drafting of this report who provided valuable input on its content but do not necessarily concur with its recommendations: Janice Plante, Public Affairs Officer, New England Fishery Management Council; Alexa Cole, Director, NOAA Fisheries Office of International Affairs, Trade, and Commerce; and Lieutenant Commander David Stutt, US Coast Guard.

Report Layout and Design: Kelly Cochrane-Collar, Mad River Creative

Suggested Citation

Emily J. Speigel & Laurie J. Beyranevand, Vt. L. & Grad. Sch. Ctr. for Agric. and Food Sys., Seafood Fraud: Analysis of Legal Approaches in the United States (2022), https://www.vermontlaw.edu/sites/default/files/2022-06/seafood-fraud-analysis-us-legal-approaches_20220627_1153.pdf.